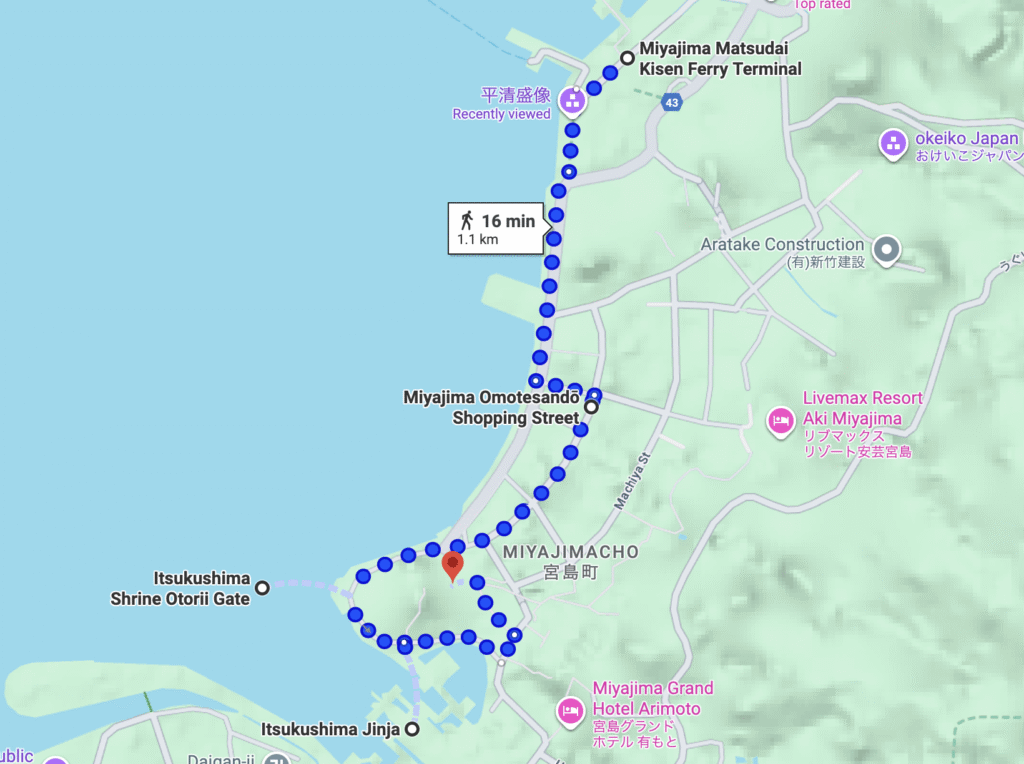

<ツアー概要> ツアー時間:2時間 宮島フェリーターミナル前(集合)https://maps.app.goo.gl/QtW6wDxyTPFcYk749

1.表参道商店(1時間程度) ・食べ歩き(もみじ饅頭・牡蠣・穴子など) ・費用はお客様負担

2.厳島神社(30分程度) ・干潮時は鳥居の下まで行き説明する ・有料ゾーンへの入場はなし・希望される場合はゲスト負担

3.千畳閣(解散) ・中に入って説明後解散 ・お客様には景色を楽しんでいただく

立替金等:千畳閣入場料 100円/人 現金のみ ※飲食代はお客様負担

表参道商店街 OMOTESANDO SHOPPING STREET

Background & Significance

Year Established: Developed gradually from the Edo period (1603-1868) as a pilgrimage route

Purpose of Construction: This street was created as the main approach to Itsukushima Shrine. “Omotesando” literally means “front approach path” – it’s the official route that pilgrims and visitors take to reach the shrine.

Development:

- Started as a simple path for religious pilgrims during the Edo period

- Gradually developed into a commercial street with shops serving pilgrims’ needs (food, souvenirs, accommodations)

- After WWII, modernised while maintaining a traditional atmosphere

- Today has over 70 shops in a 350-meter stretch

Current Use & Significance: The street remains the main shopping area of Miyajima, selling local specialities, crafts, and street food. It perfectly balances commercial activity with spiritual purpose – you’re literally walking the same path pilgrims have walked for centuries to reach the sacred shrine.

Guide Talk Example:

“Welcome to Omotesando Shopping Street! This charming street has been the main path to Itsukushima Shrine for over 400 years. ‘Omotesando’ means ‘front approach,’ and you’re walking the exact same route that pilgrims took during the Edo period – that’s from 1603 to 1868, when Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa shogun family.

Back then, visiting Miyajima was a once-in-a-lifetime journey for many people, so this street developed to serve their needs – offering food, rest, and souvenirs. Today, it keeps that tradition alive! You’ll find about 70 shops here selling everything from traditional crafts to delicious street food.

Now, let me introduce you to some local specialties you must try here…”

Local Food Guide

1. Momiji Manju (もみじ饅頭)

What it is: A maple leaf-shaped cake filled with sweet bean paste (or modern flavors like custard, chocolate, cheese)

History: Created in the early 1900s (Meiji period) when a local confectioner was inspired by the beautiful maple leaves on Miyajima

Where to try: Look for shops offering freshly fried momiji manju – it’s crispy outside, warm and soft inside!

Guide Talk:

“This is momiji manju – ‘momiji’ means maple leaf, and you can see it’s shaped like one! It was invented here about 100 years ago. The traditional filling is sweet red bean paste, but now you can find many modern flavors. The special thing to try here is揚げもみじ (age-momiji) – that’s deep-fried momiji manju. It’s crispy on the outside and the warm filling melts in your mouth. It’s a perfect example of how Miyajima respects tradition while creating new experiences!”

2. Grilled Oysters (焼き牡蠣)

What it is: Fresh oysters grilled on the spot

Why Miyajima: The waters around Miyajima are famous for producing some of Japan’s best oysters due to the mix of fresh river water and seawater, plus the rich nutrients from the Seto Inland Sea

Season: Best from October to March, but available year-round

Guide Talk:

“Hiroshima Prefecture produces about 60% of Japan’s oysters, and Miyajima’s oysters are especially famous! The secret is the water – fresh water from rivers mixes with seawater here, creating the perfect environment. These oysters are plump, creamy, and have a sweet taste. You can try them grilled, fried, or even raw. I recommend the grilled ones from the street stalls – watching them cook right in front of you is part of the experience!”

Oyster Vending Machines (牡蠣の自販機)

What it is: Refrigerated vending machines selling fresh oysters in their shells, shucked oysters, and sometimes oyster products

Where to find: 宮島おもてなしトイレ内

Background:

- Purpose: Allows customers to buy fresh oysters even when shops are closed, and provides contactless purchasing

- Features: Refrigerated (or frozen) oysters in shells, shucked oysters, and related products

- Significance: Demonstrates the depth of Hiroshima’s oyster culture and the innovative spirit of applying modern technology to traditional foods

Why it’s interesting: Japan is famous for its vending machine culture (you can buy almost anything from vending machines here!), but oyster vending machines are unique even in Japan. It shows how seriously Hiroshima takes its oyster culture.

Guide Talk:

“Now, let me tell you about one of the most unique and modern aspects of Miyajima’s oyster culture – the oyster vending machine!

Japan is famous for having vending machines everywhere – drinks, snacks, even hot ramen. But Miyajima takes it to another level: you can buy fresh oysters from a vending machine, 24 hours a day!

These refrigerated vending machines sell oysters in their shells, ready to take home and cook. This is a perfect example of how Japanese innovation meets tradition. Hiroshima people are so passionate about their oysters that they created a way to make them available anytime, anywhere.

Think about it – this represents two important Japanese cultural elements:

- Vending machine culture – Japanese trust in automated systems and convenience

- Oyster culture – Hiroshima’s pride in their oysters is so strong that they ensure fresh oysters are accessible 24/7!

For tourists, it’s a fascinating photo opportunity and a symbol of how traditional foods can be preserved and shared using modern technology. If you spot one of these machines at the ferry terminal or around the island, definitely take a photo – your friends back home won’t believe it!”

3. Anago-don (穴子丼 – Conger Eel Rice Bowl)

What it is: Grilled conger eel on rice, glazed with sweet-savory sauce

Why special: Miyajima’s anago is caught fresh from the Seto Inland Sea and is known for being tender and not too fatty

Guide Talk:

“If you want a full meal, try anago-don! Anago is conger eel – it’s different from the eel you might know (unagi). Miyajima’s anago is lighter, more delicate, and incredibly tender. It’s grilled with a sweet soy-based sauce and served over rice. Many shops here have been making it the same way for generations.”

4. Nigiri-Ten (握り天 – Fried Fish Cake Sticks)

What it is: Fish paste (surimi) mixed with various ingredients, shaped into stick form, and deep-fried. It’s a type of “satsuma-age” (fish cake), but Miyajima-style nigiri-ten is famous for being freshly fried to order in a convenient stick shape.

Special features:

- Made fresh when you order – served piping hot!

- Wide variety of fillings: octopus, shrimp, cheese, potato butter, whole oysters, and more

- Perfect for eating while walking (te-bura – hand food)

- Represents Miyajima’s fishing tradition combined with modern street food culture

Why Miyajima: With abundant seafood from the Seto Inland Sea, Miyajima has a long tradition of processing fish into various preserved and cooked forms. Nigiri-ten represents traditional fish-processing wisdom meeting contemporary gourmet street food.

Guide Talk:

“If you’re hungry while walking this street, you absolutely must try nigiri-ten! Nigiri-ten is fish paste shaped into a stick and deep-fried – think of it as a hot, crispy fish cake on a stick.

What makes it special here is the incredible variety of fillings and the fact that they fry it fresh when you order. You’ll find stalls with dozens of options displayed: traditional ones with octopus or shrimp, modern fusion ones with cheese or potato-butter, and even some with a whole oyster inside!

The texture is amazing – crispy and golden on the outside, fluffy and flavorful on the inside. It’s the perfect example of how Miyajima takes its abundant seafood and transforms it into delicious, convenient street food.

This connects to Miyajima’s fishing heritage. Before refrigeration, people needed ways to preserve and process fish. These fish cake traditions have evolved into today’s creative, delicious street snacks. I recommend trying at least two different flavors – maybe one traditional and one modern!”

Miyajima Crafts – Wood Carving Tradition

Background & Significance:

Historical context: While kokeshi dolls originated in the Tohoku region (northeastern Japan), Miyajima has its own rich tradition of woodcraft called “Miyajima-zaiku” (宮島細工). This woodworking tradition developed because:

- The island’s sacred forests provided quality wood

- Pilgrims visiting the shrine wanted souvenirs

- Local craftsmen developed specialized techniques over centuries

Miyajima Kokeshi – Modern interpretation:

- Combines traditional Tohoku kokeshi style with Miyajima-specific motifs

- Features designs unique to Miyajima: shrine maidens (miko), deer, Taira no Kiyomori, the torii gate, and other island symbols

- Represents how traditional crafts evolve by incorporating local identity

- Blends traditional woodworking skills with modern “kawaii” (cute) culture

Traditional Miyajima woodcrafts include:

- Rice scoops (shamoji) – Miyajima’s most famous traditional product

- Carved trays and boxes

- Decorative items with intricate designs

Guide Talk:

“Besides food, Omotesando Street is full of wonderful souvenirs, and I want to highlight Miyajima’s woodcraft tradition.

Miyajima has been famous for woodworking for centuries. We call it ‘Miyajima-zaiku’ – Miyajima woodcraft. The island’s forests provided excellent wood, and skilled craftsmen developed techniques to create beautiful, practical items for pilgrims visiting the shrine.

The most famous traditional item is the shamoji – a rice scoop. Legend says it was invented here about 200 years ago by a monk who had a divine vision! The shamoji became Miyajima’s symbol, and you’ll see giant ones around the island. People believe it brings good luck and ‘scoops up’ good fortune.

Now, look at the shops – you’ll notice adorable wooden dolls called Miyajima kokeshi. Kokeshi dolls originally come from northeastern Japan, but Miyajima’s craftsmen put their own spin on them. Instead of traditional designs, Miyajima kokeshi feature:

- Shrine maidens in traditional red and white robes

- Cute deer with their characteristic spots

- The iconic red torii gate

- Even historical figures like Taira no Kiyomori!

These dolls are small, colorful, and have a modern, cute aesthetic. They’re perfect examples of how traditional craft techniques meet contemporary ‘kawaii’ culture – that’s the Japanese concept of cuteness that’s popular worldwide now.

What I love about these is that they tell Miyajima’s story through traditional woodworking skills. Each one is handcrafted using techniques passed down through generations, but with designs that speak to today’s visitors.

If you’re looking for a meaningful souvenir that connects you to both Miyajima’s craft heritage and its spiritual character, these wooden items are perfect. They’re practical, beautiful, and carry the spirit of the island’s artisan tradition.”

Key Points to Mention:

- This street connects the ferry pier to the shrine – you’re walking a pilgrimage route

- The mix of sacred and commercial is typical of Japanese shrine culture

- Local food culture reflects Miyajima’s island geography (seafood) and spiritual heritage (sweets for offerings)

- Woodcraft tradition (Miyajima-zaiku) – centuries-old heritage, famous for rice scoops (shamoji) and modern kokeshi dolls

- Street food variety – from traditional (oysters, anago) to innovative (cheese nigiri-ten, fried momiji)

- Oyster vending machines – unique symbol of Hiroshima’s oyster passion meeting Japanese vending machine culture

- Encourage trying at least 2-3 items – it’s about experiencing local food culture, not just eating

- Shopping etiquette: It’s okay to browse, photos are usually fine, ask before eating while walking

- Craft shops – look for authentic Miyajima-made items vs. mass-produced souvenirs (guides can point out the difference)

厳島神社 ITSUKUSHIMA SHRINE

Construction History

Year Built: 593 CE (first established), current structure from 1168

Purpose of Construction: Built to worship three female deities (goddesses) of the sea: Ichikishimahime, Tagorihime, and Tagitsuhime. The local ruler Taira no Kiyomori, who was one of the most powerful samurai leaders in Japan during the 12th century, reconstructed the shrine in its current grand scale to pray for his clan’s prosperity and safe sea voyages.

Development:

- 593: First shrine established by Saeki Kuramoto, a local ruler

- 1168: Taira no Kiyomori (powerful samurai leader) rebuilt and expanded the shrine to its current magnificent scale

- 1207: Main hall damaged by fire, rebuilt in 1227

- 1325: Another major fire, rebuilt in 1371

- 1407 & 1599: Further fires and reconstructions (wooden buildings on water face constant challenges!)

- 1996: Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Ongoing: Regular maintenance and occasional rebuilding of sections – the shrine is constantly cared for

Current Use & Significance: Still functions as an active Shinto shrine where people come to pray, especially for maritime safety, business success, and the arts (music and dance). It’s one of Japan’s most important cultural and spiritual sites, receiving millions of visitors annually. The shrine represents the Japanese concept of harmony between human creation and nature.

Architectural Style Explanation

Shinden-zukuri Style:

“This shrine is built in a style called ‘shinden-zukuri,’ which was originally used for aristocratic residences in the Heian period (794-1185) – think of it as the architectural style of the imperial court. What makes it special:

- Built over water: The shrine appears to ‘float’ on the sea at high tide. This creates a boundary between the sacred and human worlds.

- Covered corridors: These connect different buildings and are designed to withstand the rise and fall of tides

- No walls: Traditional Japanese architecture uses pillars and open spaces rather than walls, creating harmony with nature

- Red color (vermilion): In Shinto belief, this red color wards off evil spirits and symbolizes life and vitality

- Cypress bark roof: The roof is made from layers of cypress bark – a traditional, expensive material that needs replacement every 10-15 years

The Floating Torii Gate:

The great torii gate stands 16 meters (about 52 feet) tall and weighs approximately 60 tons. It’s not buried or anchored – it stands by its own weight! The current gate is the 9th generation, rebuilt in 1875. At high tide, it appears to float on water; at low tide, you can walk up to it.”

Guide Talk Example:

“Welcome to Itsukushima Shrine, one of Japan’s most sacred sites and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1996. The name ‘Itsukushima’ means ‘island where gods are worshipped,’ and you’re going to see why this place is so special.

The shrine was first built in 593 CE – that’s about 1,400 years ago – but the current structure was created in 1168 by Taira no Kiyomori. He was one of the most powerful samurai warlords in Japanese history, and he expanded this shrine to show his power and devotion.

Now, what makes this shrine absolutely unique is that it’s built over the water. The whole building is standing on a platform supported by pillars driven into the seabed. The ancient Japanese believed this entire island was sacred, so they couldn’t build directly on the land. Their solution? Build over the water! This way, ordinary people could worship without stepping on holy ground.

Notice how the shrine appears to float, especially at high tide. This creates a symbolic boundary between the human world and the divine world. The covered corridors we’re walking through are designed to move slightly with the tides – there are small gaps between the floorboards to let water flow through during high tide and storms.

See that beautiful red color? It’s called ‘vermilion,’ and in Shinto belief, it protects against evil spirits and represents vitality. The roofs are made from cypress bark – a premium material that’s been used in Japanese sacred architecture for over a thousand years.

The shrine has burned down and been rebuilt several times over the centuries – wooden buildings near the sea face constant challenges! But each time, it’s been faithfully reconstructed using traditional methods. This is the Japanese concept of preservation: not keeping the original physical materials forever, but keeping the form, technique, and spirit alive through continuous renewal.”

The Torii Gate – Special Explanation

Guide Talk:

“Now, let’s talk about that magnificent gate you see in the water – the O-torii, or Great Torii Gate. It’s probably the most photographed spot in Miyajima!

This gate marks the boundary between the spiritual world and our world. In Shinto, torii gates are found at the entrance to sacred spaces. This one is extra special because it stands in the sea.

Here are some amazing facts:

- It’s 16 meters tall – about as high as a 5-story building!

- It weighs 60 tons – that’s about 40 cars!

- It’s not anchored or buried – it stands by its own weight. The wooden legs are simply placed in stone foundations on the seabed, and gravity holds it in place.

- The current gate was built in 1875, making it about 150 years old. It’s actually the 8th generation of torii gates here.

- It’s made from camphor wood, which is resistant to water and insects.

The experience changes with the tide. At high tide – like now/later today – the gate appears to float on water, and boats used to pass through it during ceremonies. At low tide, you can walk right up to it on the sand. Both views are beautiful in different ways!

People used to believe that passing through this gate purified them before approaching the shrine. Even today, seeing it fills people with a sense of awe and reverence.”

Key Points to Mention:

- The whole island is sacred – that’s why the shrine is built over water (explain this concept clearly)

- UNESCO World Heritage Site (1996) – recognized for outstanding universal value

- Active shrine – people still worship here, so remind visitors to be respectful (no loud talking, follow photo rules)

- Tides change everything – explain that the experience is different at high vs low tide

- The three goddesses – daughters of Susanoo (god of storms and sea), worshipped for protection of sailors and fishermen

- Taira no Kiyomori – briefly explain he was like the “president” or most powerful leader of Japan in the 1100s before the samurai government was established

- Fires and rebuilding – this shows the Japanese philosophy of preservation through renewal, not just keeping old things

- Noh theater stage – point out the stage over water (if visible), one of only three Noh stages built over water in Japan

- Photography etiquette – photos usually okay except inside certain buildings (follow signs), be mindful during prayer times

Shinto Worship Basics (for visitor questions):

“If you’d like to pray at the shrine like locals do, here’s how:

- Bow slightly before approaching

- Ring the bell gently (to announce yourself to the gods)

- Toss a coin in the offering box (5 yen is traditional – the word for 5 yen sounds like ‘connection’ in Japanese)

- Bow twice deeply

- Clap twice

- Make your prayer silently

- Bow once more

- Step back

You don’t have to do this, but you’re welcome to experience it if you’d like!”

The Sacred Horse (Shinme/神馬) – ADD THIS SUBSECTION

Location: Near the entrance of the shrine corridors (eastern side, near current exit area), in a small structure called “o-umaya” (御厩 – sacred stable) or “shinme-sha” (神馬舎 – sacred horse hall)

Background & Significance

What is a Shinme (Sacred Horse)?

Since ancient times in Japan, horses have been considered “vehicles for the gods” – divine transportation that allowed deities to move between the heavenly and earthly realms.

Historical Practice:

- Origin: People would donate living horses to shrines as sacred offerings to the gods

- Purpose: The horse would become the deity’s mount and live at the shrine

- Evolution: Because maintaining living horses was expensive and difficult, over time people began offering horse statues (wooden or clay) instead

- Current practice: Most shrines now display wooden horse statues in a small stable structure near the entrance

The Ema Connection: The word “ema” (絵馬) literally means “picture-horse.” These wooden prayer plaques that you see hanging throughout Japanese shrines originated from this horse-offering tradition:

- People who couldn’t afford to donate a real horse would instead offer a wooden plaque with a horse painted on it

- Over time, the paintings expanded beyond horses to include other images

- Today, ema are used for writing prayers and wishes, but the name still honors their origin as horse offerings

Itsukushima Shrine’s Sacred Horse – Special Stories

The White Horse Mystery:

Itsukushima Shrine has a fascinating legend about its sacred horses:

- The Legend: No matter what color the donated horse was originally – brown, black, spotted – after living at the shrine for some time, it would mysteriously turn completely white

- This white transformation was seen as proof of the island’s divine power and the gods’ presence

- White horses are especially sacred in Shinto belief, symbolizing purity and divine favor

Historical Reality:

- Until several decades ago (mid-20th century), Itsukushima Shrine actually kept real living horses in the stable

- Visitors could see these sacred horses during their shrine visits

- The current white wooden horse statue replaced the living horses, but maintains the tradition and commemorates the legend

Current Display:

- The white wooden horse you see today sits in a small stable-like structure

- It faces toward the main shrine buildings, as if ready to serve the deities

- Many visitors bow respectfully to the sacred horse as they enter or exit the shrine

Guide Talk Example

Timing: As you approach or pass the sacred horse stable near the entrance

“Before we enter the main shrine area, let me point out something special here – this is the shinme-sha, the sacred horse hall. Inside, you’ll see a beautiful white wooden horse.

In Japanese Shinto tradition, horses are considered ‘vehicles for the gods’ – divine transportation that allows deities to travel between heaven and earth. For over a thousand years, people donated living horses to shrines as sacred offerings.

Now, here’s where Itsukushima Shrine’s story becomes particularly fascinating. There’s an ancient legend that any horse donated to this shrine – whether it was brown, black, or any other color – would mysteriously turn completely whiteafter living here for some time. People believed this transformation proved the divine power of the island and the presence of the gods.

Can you imagine? Visitors would arrive and see a dark horse, then return years later to find it had become pure white! White horses are especially sacred in Shinto because white symbolizes purity and divine favor.

Until the mid-1900s – not that long ago – real living horses actually lived in this stable. Visitors could see them during their shrine visit. The wooden horse you see now replaced the living horses, but it keeps the tradition alive and commemorates that mysterious legend.

Now, here’s something that connects to modern shrine culture: Have you noticed the wooden plaques called ‘ema’hanging throughout the shrine? The word ‘ema’ literally means ‘picture-horse.’ These prayer plaques originated from this exact tradition!

In ancient times, people who couldn’t afford to donate a whole horse would offer a wooden board with a horse painted on it instead. Over centuries, the pictures expanded to show many different images, but we still call them ‘ema’ – honoring their origin as horse offerings. Every time you see someone writing their wish on an ema, they’re participating in a tradition that goes back to these sacred horses!

So this small stable connects several important aspects of Japanese shrine culture: the sacredness of horses, the legend of divine transformation, and even the prayer plaques we see today.”

豊国神社/千畳閣 TOYOKUNI SHRINE / SENJOKAKU

Construction History

Year Built: 1587 (late 16th century)

Purpose of Construction: Commissioned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the three “Great Unifiers” of Japan who ended a century of civil war and unified the country. He ordered this hall to be built as a Buddhist scripture hall where monks would read sutras (Buddhist prayers) for the souls of fallen warriors who died in battle. Think of it as a memorial and prayer hall for the war dead.

Development:

- 1587: Construction began under Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s order

- 1598: Hideyoshi died suddenly, and construction stopped immediately – the building was left unfinished as a sign of respect/mourning

- Unfinished for over 400 years – never completed as originally planned

- Edo period (1603-1868): Used informally as a gathering space despite being incomplete

- Meiji period (1868-1912): When Buddhism and Shinto were officially separated by government order, the building was converted to a Shinto shrine and dedicated to Toyotomi Hideyoshi himself

- 1872: Renamed “Toyokuni Shrine” (Shrine of the Bountiful Country) in Hideyoshi’s honor

- Today: Preserved as an Important Cultural Property, nicknamed “Senjokaku” (Hall of 1,000 Tatami Mats)

Current Use & Significance: Now functions as a Shinto shrine dedicated to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Visitors can enter the vast hall, enjoy the ocean views, and see the many wooden prayer plaques (ema) hanging inside. It’s a peaceful retreat from the busier shrine areas and offers some of the best views of the torii gate and Seto Inland Sea. The unfinished nature of the building makes it a unique historical artifact – a literal “frozen moment” in time.

Architectural Style Explanation

Buddhist Hall Architecture (未完成 – Unfinished):

“This building was designed as a Buddhist sutra hall, so it follows traditional Buddhist temple architecture rather than shrine style. Here’s what makes it special:

- Massive scale: About 857 tatami mats in size (hence the nickname ‘Senjokaku’ – Hall of 1,000 Mats). That’s roughly 1,400 square meters or about 15,000 square feet – imagine the size of a basketball court and a half!

- Unfinished state: Look carefully – there are no ceilings, no walls in some sections, unpainted wood in places. This isn’t decay; it was literally left incomplete when Hideyoshi died.

- Open-air feeling: The lack of completion created an accidentally beautiful space – the open sides and high roof create amazing ventilation and light

- Wooden plaques (ema): Hundreds of votive plaques hang from the ceiling, left by visitors over centuries

- Five-story pagoda next door: The beautiful pagoda right beside Senjokaku was built earlier (1407) and survived many disasters that Senjokaku would have faced if completed

Design note: The openness and unfinished wood have aged beautifully, creating a rustic, contemplative atmosphere that many visitors find even more moving than a completed building would have been.”

Guide Talk Example:

“Welcome to Senjokaku, which means ‘Hall of 1,000 Tatami Mats!’ This is one of Miyajima’s most fascinating buildings because of its unusual story.

This hall was commissioned in 1587 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi – one of the most important figures in Japanese history. Let me give you some context: In the 1500s, Japan was torn apart by civil war for over 100 years. Different samurai lords fought each other for power. Hideyoshi was a brilliant warrior and leader who managed to unify the entire country and end the wars. He rose from being a peasant farmer’s son to becoming the supreme ruler of Japan – an incredible story!

After decades of warfare, Hideyoshi wanted to build this hall as a place where Buddhist monks would pray for the souls of all the warriors who died in battle – on all sides, not just his own. This shows an important aspect of Japanese Buddhism: praying for all the dead, even former enemies, to find peace.

Construction began in 1587, but in 1598, Hideyoshi suddenly died. Out of respect and mourning, construction stopped immediately, and the building was left exactly as it was. For over 400 years, it has remained unfinished.

Now, look around you. Notice anything unusual? There’s no ceiling in most places – you can see straight up to the roof beams. Some walls are missing. The wood is unpainted. These aren’t signs of neglect – this is exactly how it looked when work stopped in 1598!

The building’s name ‘Senjokaku’ comes from its size – about 857 tatami mats, which they rounded up to ‘a thousand mats.’ To give you a sense of scale, this is one of the largest wooden buildings in this region. The open sides and high ceiling create beautiful natural ventilation, and you can feel the sea breeze flowing through.

In 1872, during the Meiji period when Japan was modernizing rapidly, the government ordered the separation of Buddhism and Shinto – two religions that had been mixed together for centuries. This building was converted from a Buddhist hall into a Shinto shrine and dedicated to Hideyoshi himself. So now he’s worshipped here as a deity! That’s why it’s officially called ‘Toyokuni Shrine’ – ‘Shrine of the Bountiful Country.’

Look up at the ceiling – see all those wooden plaques? Those are called ‘ema,’ prayer plaques. People have been leaving them here for hundreds of years, each one carrying someone’s wish or prayer. Some are very old; some were left just recently. Many show ships and boats, reflecting prayers for safe sea voyages.

Now, let me take you to the viewing area. From here, you get one of the best views on the island…”

Viewing Platform – Guide Talk:

“This is one of my favorite spots on Miyajima! From here, you can see:

- The famous torii gate standing in the water – this elevated view gives you a different perspective than seeing it from the shore

- The Seto Inland Sea – this sea has over 3,000 islands and has been a major trade route for thousands of years

- The five-story pagoda next to us – built in 1407, mixing Japanese and Chinese Buddhist architectural styles. It’s beautifully preserved!

- Itsukushima Shrine’s red corridors winding along the coast

- The forested mountains behind us – Mount Misen, Miyajima’s highest peak at 535 meters (1,755 feet)

Depending on the season you visit:

- Spring: Cherry blossoms frame this view (late March-early April)

- Summer: Deep green forests and clear blue waters

- Autumn: The island lives up to its ‘Momiji-dani’ name with spectacular red maple leaves (November)

- Winter: Clear, crisp views and sometimes snow on the mountains

This peaceful spot is where you can really feel the combination of natural beauty and human spiritual devotion that makes Miyajima special. Take a moment to sit, breathe, and enjoy the view. The sea breeze and the quiet of this space offer a nice contrast to the busier areas we visited earlier.”

Key Points to Mention:

- Toyotomi Hideyoshi – explain he was one of Japan’s three great unifiers (along with Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu), ended civil war, unified Japan in the 1580s-1590s

- Left unfinished – this is intentional/historical, not neglect; stopped when Hideyoshi died in 1598

- Converted from Buddhist to Shinto – explains why it looks like a temple but functions as a shrine (1872 government order)

- Senjokaku nickname – explain tatami mat measurement (one tatami = about 1.65 square meters)

- Peaceful retreat – emphasize this is a quieter, more contemplative space compared to the main shrine

- Best photo spot – the viewing area offers panoramic views perfect for photos

- The five-story pagoda – mention it briefly, built 180 years before Senjokaku, beautiful example of Buddhist architecture

- Prayer plaques (ema) – centuries of accumulated prayers create a visual history

- Architectural accident – the unfinished state created a beautiful, airy space that might not have existed if completed

Cultural Context to Share:

“The unfinished nature of Senjokaku teaches us something interesting about Japanese culture. In the West, we might finish the building later or tear it down. But here, they preserved it exactly as it was when Hideyoshi died, as a form of respect and as a historical record. This shows the Japanese value of maintaining historical memory and accepting imperfection. There’s actually a aesthetic concept in Japan called ‘wabi-sabi’ – finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence. Senjokaku embodies this perfectly!”

Common Questions & Answers:

Q: Can we go inside the torii gate?

A: At low tide, you can walk out on the sand to reach it. At high tide, it’s surrounded by water. Historically, boats would pass through it during ceremonies.

Q: Why is the island sacred?

A: Ancient Japanese believed powerful natural formations (mountains, islands, forests) housed kami (gods/spirits). Miyajima’s dramatic beauty made people feel divine presence, so the whole island became sacred.

Q: What’s the difference between a shrine and a temple?(→『関東ツアー 浅草〜合羽橋』マニュアルに詳しい解説記載あり)

A: Shrines are Shinto (Japan’s indigenous religion, focused on nature spirits). Temples are Buddhist (came from India via China/Korea). You’ll see both on Miyajima. Generally: shrines have torii gates, temples have larger main halls and pagodas.

Q: Is it okay to pray even if we’re not Shinto?

A: Yes! Shinto is inclusive. You’re welcome to participate or simply observe respectfully.

Q: What’s the best time to visit?

A: Each season has its charm. Avoid peak tourist times (March-April cherry blossoms, November autumn leaves, Golden Week in early May, Obon in August) if you want fewer crowds.

コメント